Listen, repeat, memorize!

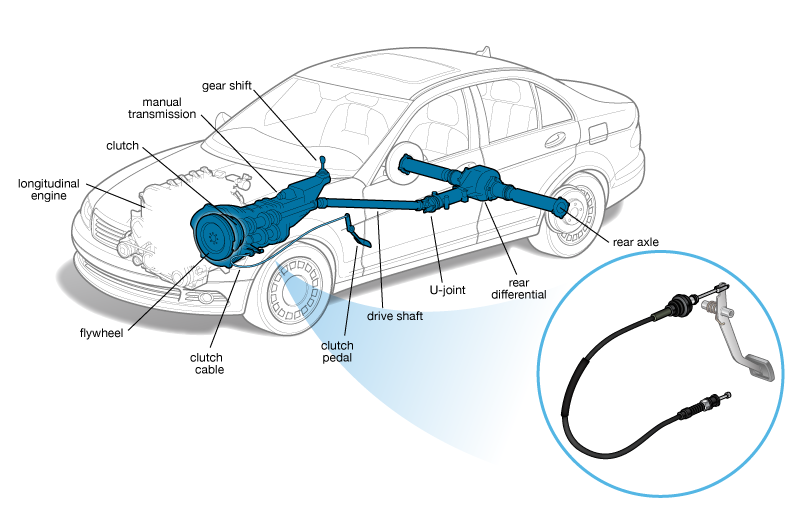

Clutch Cable

On many vehicles with manual transmissions, a steel cable connected from the clutch pedal lever to the clutch itself is what disengages the clutch when the pedal is depressed.

Pushing in the pedal pulls the steel cable, which is covered by a heavy sheath, and the cable extends to disengage the clutch and let the driver smoothly shift gears.

Hydraulic clutches don’t have cables. Instead, pushing in the clutch pedal forces fluid to flow from a master cylinder to a “slave cylinder” that moves the pressure plate and disengages the clutch.

Some older clutches have mechanical linkage with rods and levers instead of a cable.

Clutch cables usually last for years, but they can fray or break.

Signs of wear include the clutch pedal becoming harder to push down or not springing back up when released (which could also be caused by a worn or broken return spring).

Cables can also loosen or stretch from use so that the clutch doesn’t fully release when the pedal is pushed all the way in.

Listen to the Text:

Listen, repeat, memorize!

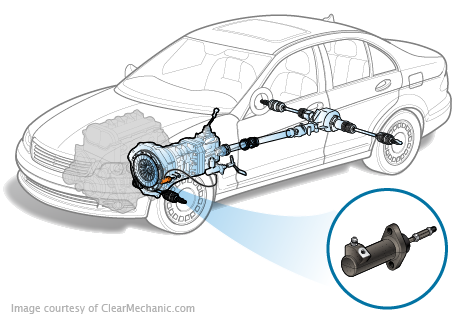

Clutch Slave Cylinder

Hydraulic clutches for manual transmissions use brake fluid to supply pressure to disengage the clutch from the engine.

Pushing in the clutch pedal makes fluid flow from a master cylinder (or fluid reservoir) to the slave cylinder, which moves the pressure plate, allowing the driver to shift gears.

Seals and hoses can leak, and if enough fluid doesn’t reach the slave cylinder the clutch pedal may go all the way to the floor or the driver may not be able to shift gears.

Air can also get into the hydraulic system, causing the clutch pedal to feel spongy.

Some slave cylinders are mounted on the outside of a manual transmission, while others are inside the transmission bell housing.

The clutch slave cylinder transforms hydraulic pressure into a force on the clutch release lever, in order to operate the clutch.

The slave cylinder is mounted on the transmission, and are also usually manufactured from engineering plastics to achieve optimum cost and weight.

Listen to the Text:

Listen, repeat, memorize!

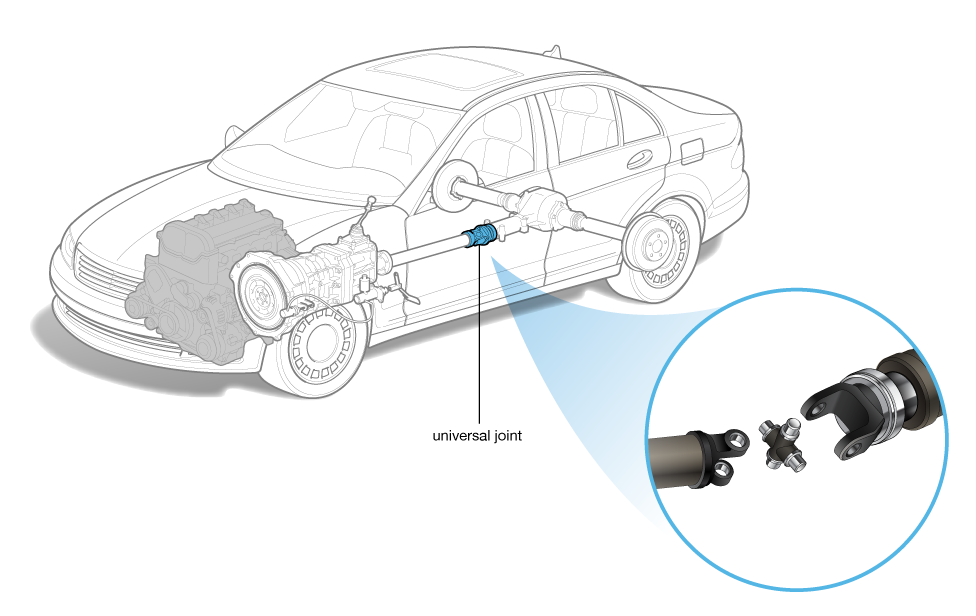

Universal Joint

Universal joints allow drive shafts to move up and down with the suspension while the shaft is moving so power can be transmitted when the drive shaft isn’t in a straight line between the transmission and drive wheels.

Rear-wheel-drive vehicles have universal joints (or U-joints) at both ends of the drive shaft.

U-joints connect to yokes that also allow drive shafts to move fore and aft as vehicles go over bumps or dips in the road, which effectively shortens or lengthens the shaft.

Front-drive vehicles also use two joints, called constant velocity (or CV) joints, but they are a different kind that also compensate for steering changes.

On rear-drive vehicles, one sign of a worn U-join is a “clank” sound when a drive gear is engaged.

On front-drive vehicles, CV joints often make a clicking noise when they’re worn. CV joints are covered by protective rubber boots, and if the boots crack or are otherwise damaged, the CV joints will lose their lubrication and be damaged by dirt and moisture.

Listen to the Text:

Listen, repeat, memorize!

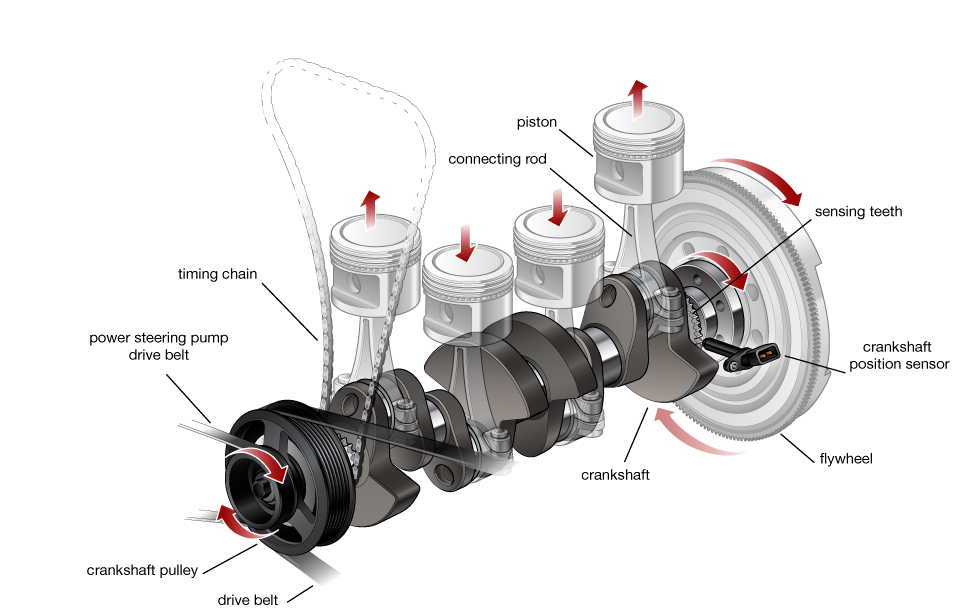

Crankshaft (Part 2)

A crankshaft usually connects to a flywheel. The flywheel smooths out the rotation.

Sometimes there is a torsion or vibration damper on the other end of the crankshaft.

This helps to reduce vibrations of the crankshaft. Large engines usually have several cylinders.

This helps to reduce pulsations from individual firing strokes.

For some engines it is necessary to provide counterweights. The counterweight is used to offset the piston and improve balance.

While counterweights add a lot of weight to the crankshaft, it provides a smoother running engine.

This allows higher RPMs to be reached and more power produced.